Should warm-ups be brief, extended, gentle or intense? Matt Long and Jamie French sift through the evidence

Jog, stretch, drills and strides. For most athletes, a warm-up includes these four elements in one order or another.

But a new concept has taken hold in recent seasons: the extended warm-up.

Hicham El Guerrouj, who famously took 1500m and 5000m gold at the 2004 Athens Olympics, was among the first high-profile advocates of the controversial approach, reportedly performing strides of between 200m-300m before a session or race.

A growing number of athletes now use much longer strides of between 200m-400m at race pace, to fire their system 10-20 minutes before they start.

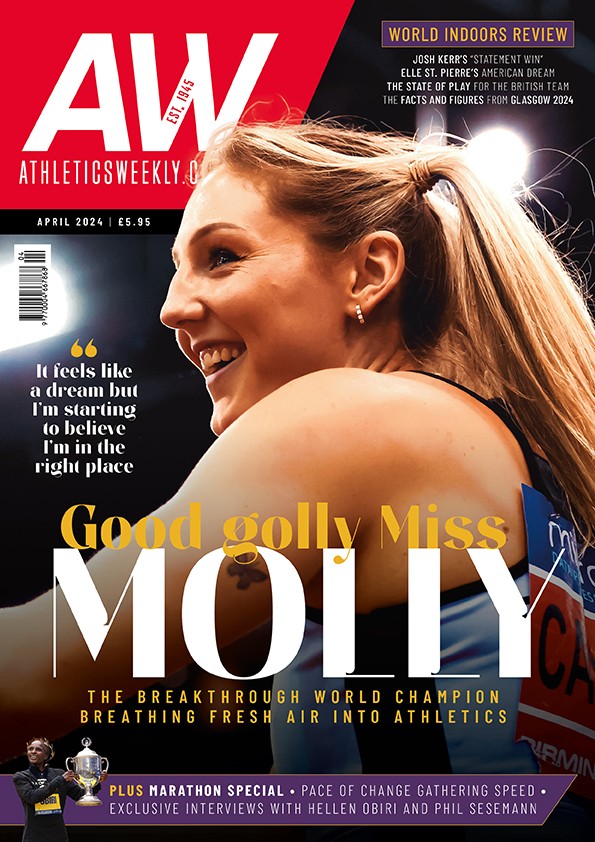

Fans of the approach include multiple British record-holder Laura Muir (pictured) whose coach, Andy Young, prescribes them before races.

“I have used higher intensity warm-ups for Laura Muir for middle distance races,” Young says. ”I guess their value is they get the body ready for intense exercise. It’s because the body has already generated lactate and you are ready for it.”

Aaron Thomas, the sports scientist and 2015 British Milers’ Club coach of the year, says the coaching of his wife, Charlene Thomas, who won the European Team Championship 1500m in Stockholm in 2011, was underpinned by her using a higher intensity warm-up.

And BMC president Dr Norman Poole, who worked with 2010 European 800m silver medallist Michael Rimmer, also advocates warming up the long way.

Why warm up?

As well as raising your temperature and heart rate, activating key muscle groups and mobilising key joints and ranges of motion, increasing the intensity of event-specific activity is important for what sports scientists call ‘potentiation’ or firing up of nerve impulses.

In an endurance running context, athletes have traditionally used short alactic strides before training and competition to achieve such a priming effect. But plenty of research has suggested that this alone may not be enough to achieve full potentiation.

Why longer might be better

The answer lies in an understanding of what we call V02 kinetics. In simple terms this is how quickly you can get the right amount of oxygen to where it needs to be at the start of exercise. When you next line up in that cross country race or indoor meeting, energy turnover in muscles and metabolic rates increases up to 10-fold within the first few seconds of the gun being fired.

The problem, however, is that the speed at which the O2 consumed is effectively used as a fuel in the production of ATP can take up to 2-3min to reach a constant steady state. For the duration of this period, there is a deficit of oxygen and the body produces energy anaerobically which is inefficient and has the potential detrimental effect of interfering with the energy production later in the same race.

Evidence suggests a higher intensity warm-up can help to counteract this. “From a physiological point of view it’s about priming the enzyme systems,” Thomas explains. “It’s about stimulating the metabolic pathways to work.”

But there’s more to it. Research funded by the British Milers’ Club and carried out at Leeds Beckett University, found that a longer and higher intensity warm-up may have psychological benefits in terms of engendering a sense ‘readiness’ for the race or tough training session.

Practicalities

Of course, when you arrive at a cross country, road or track race, space may be limited with competitions already in progress. For this reason, says Young, you must be prepared to improvise.

“What I’ve tended to do is have Laura do something like 4x50m back-to-back sprints,” he continues. “She would run these at faster than her race pace. You have to use what space is available to you.”

He adds that you also need to experiment to see how long a warm-up works for you. “They do have their value but in order to be exactly sure of what they do you’d need to experiment”.

HOW TO LENGTHEN YOUR WARM-UP

» Think about the optimum timing between the conducting of a higher intensity warm-up and competition. It might be as close as 10 minutes before a race or much further away from the start of a race. Try it in training.

» Also experiment with distance of your high intensity warm-up stride. What you do before a four-mile cross country race may be very different to an 800m track race. Find what works for you.

» Increase the intensity and speed of your strides, as well as the duration. Evidence suggests they should be either at race pace or slightly faster.

» Be prepared to reflect on the psychological as well as the physiological benefits of a higher intensity warm-up in terms of the priming effect that they can exert mentally. Ask yourself, do you ‘feel’ better prepared in your head?

» Whenever we change things like warm-ups we risk something going wrong. So experiment with a higher intensity warm-up during training before you jump two feet first into competition in order to help build awareness of race pace specificity.

» Remember that what works for one athlete does not work for another. Physiologists will tell you that some people are more pre-disposed to getting the benefits of a higher intensity warm-up than others.

» England Athletics coach educators Matt Long and Jamie French won the 2013 BMC Horwill Scholarship Award for their work in this field