European Athletics president Svein Arne Hansen says “most” world and European records would have to be replaced under recommended guidelines

The European Athletics Council has accepted “revolutionary” and “radical” recommendations for the implementation of new record ratification rules.

A European records credibility project team, led by Pierce O’Callaghan, has released a report outlining why the team believed a review was required, what the options were and their recommendations. Should the new record ratification rules be implemented, European Athletics has said this would lead to the rewriting of the world and European records lists.

European Athletics’ endorsement of the plan came at the governing body’s 148th Council meeting in Paris, which was held from April 28-30.

European Athletics said that the project team’s report, which can be read in full here, will be forwarded to the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) “with the recommendation that the two organisations coordinate the implementation of new record ratification rules”.

On Monday, European Athletics also announced that its Council had accepted recommendations to revoke “a number” of European Athlete of the Year Awards and European Athletics Coaching Awards, “subject to legal review”.

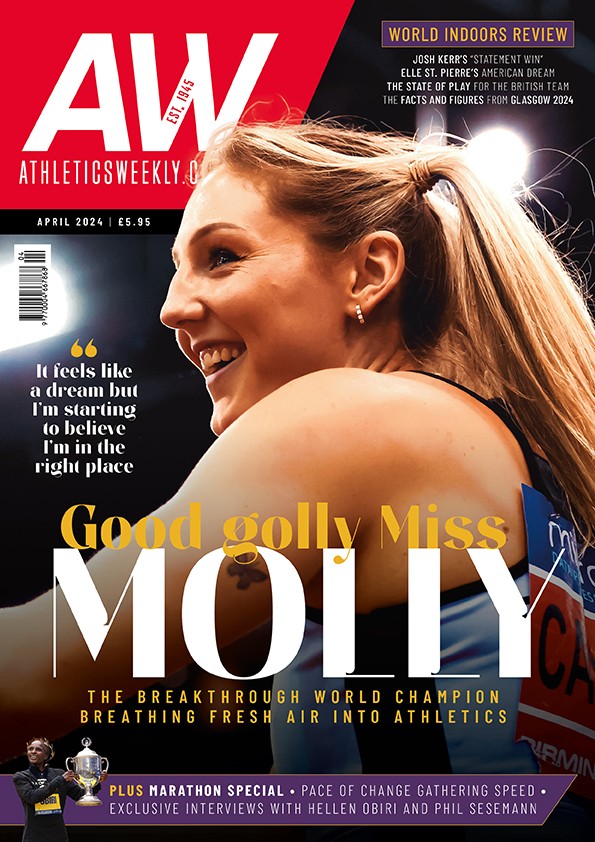

“Performance records that show the limits of human capabilities are one of the great strengths of our sport, but they are meaningless if people don’t really believe them,” said European Athletics president Svein Arne Hansen (pictured).

“What we are proposing is revolutionary, not just because most world and European records will have to be replaced but because we want to change the concept of a record and raise the standards for recognition to a point where everyone can be confident that everything is fair and above board.”

The project team’s proposals include that senior world and European records should only be recognised if certain criteria is met.

Record performances would need to have been achieved at competitions on a list of approved international events “where the highest standards of officiating and technical equipment can be guaranteed”. The athlete must also have been subject to “an agreed number of doping control tests in the months leading up to the performance”, while the doping control sample taken after the record performance would need to be stored and available for retesting for 10 years.

The project team also recommended that records can be withdrawn at any time if the athlete commits a doping or integrity violation “even if it does not directly impact the record performance”.

With Hansen stating that the IAAF started storing samples in 2005, any records set before that time could stand to be wiped under the proposed new rules.

That would include the world record marks in the triple jump and marathon set by Britain’s Jonathan Edwards in 1995 and Paula Radcliffe in 2003 respectively.

The plans have been met with mixed reaction, with Radcliffe among those to have voiced criticism on Twitter.

“I worked extremely hard for my PBs and they will always be valid to me. I know they were set through hard work and best effort and abiding by all the rules and am proud of them,” Radcliffe wrote on Monday.

“Governing bodies have a duty to protect every clean athlete, here they again fail those athletes. We had to compete against cheats, they couldn’t provide us a level playing field, we lost out on medals, moments and earnings due to cheats, saw our sport dragged through the mud due to cheats and now, thanks to those who chose to cheat we potentially lose our world and area records.”

She added: “Although we are moving forward I don’t believe we are yet at the point where we have a testing procedure capable of catching every cheat out there, so why reset at this point? Do we really believe a record set in 2015 is totally clean and one in 1995 not?

“I am hurt and do feel this damages my reputation and dignity. It is a heavy handed way to wipe out some really suspicious records in a cowardly way by simply sweeping all aside instead of having the guts to take the legal plunge and wipe any record that would be found in a court of law to have been illegally assisted.

“It is confusing to the public at a time when athletics is already struggling to market itself. How do they explain how stadium, club and national records are better than the area and world marks or will they force all those to be to wiped too?”

Some thoughts on the EAA decision today. pic.twitter.com/xpee4luvSp

— Paula Radcliffe (@paulajradcliffe) May 1, 2017

Edwards told the Guardian: “I thought my record would go some day, just not to a bunch of sports administrators. It seems incredibly wrong-headed and cowardly. And I don’t think it achieves what they want it to. Instead it cast doubts on generations of athletics performances.”

On announcing the plans, Hansen had said: “It’s a radical solution for sure, but those of us who love athletics are tired of the cloud of doubt and innuendo that has hung over our records for too long. We need decisive action to restore credibility and trust and I want to thank the project team, led by Pierce O’Callaghan, for their great work in showing us a way forward.

“This will now go to the IAAF Council meeting in August and, on behalf of European Athletics, I will be encouraging them to adopt this proposal. In the meantime we will be checking with our legal advisors to make sure the new rules will stand up to any challenges that might come.”

IAAF president Seb Coe, who attended the final session of the meeting together with other European members of the IAAF Council, said: “I like this because it underlines that we [the governing bodies] have put into place doping control systems and technology that are more robust and safer than fifteen or even ten years ago.

“Of course, for this to be adopted for world records by the IAAF it needs global approval from all Area Associations. There will be athletes, current record-holders, who will feel that the history we are recalibrating will take something away from them but I think this is a step in the right direction and if organised and structured properly we have a good chance of winning back credibility in this area.”